Reviews and news about spanish and portuguese writing authors, ibero-american cinema and arts Comments, ideas, reviews or whatever to: d.caraccioli @ yahoo.co.uk

Thursday, July 26, 2007

Monday, July 23, 2007

Alan Pauls - The Past

Ben Bollig reviews Alan Pauls' The Past.

Please visit SPLALit aStore

Argentine Literature

The past, Alan Pauls' first novel to be translated into English, has arrived with a certain amount of fanfare - including a film adaptation starring Gael Garcia Bernal, an appearance at the Edinburgh Festival and critical comparisons to Proust and Nabokov.Read More

Like Proust's epic, The Past is about memory. A twentysomething Buenos Aires couple, Rimini and Sofia, split up after 12 years together, sharing out friends, possessions and living arrangements. But there is a sticking point: their photographs. Sofia wants desperately to divide up the thousand-plus photos they have; Rimini feels repulsed by the pictures. For Sofia, the images are a visual prompt to aid her perfect memory of their years together; for Rimini, they moor him in the past.

Rimini moves on: a new, younger girlfriend, cocaine abuse, work addiction (he is the most productive of multilingual translators) and compulsive masturbation. He marries and divorces, breaks down and recovers. He even becomes a tennis coach. Sofia, meanwhile, haunts him with recollections at pivotal moments in his life. By the final section of the novel she has become the founder member of a remarkable organisation: the Women Who Love Too Much.

A large proportion of the text digresses from this main narrative: the life and works of a fictional painter and pioneer of 'Sick Art', Jeremy Riltse (one of his pieces involves an attempt to have part of his rectum removed and attached to canvas); the tale of the adman who brings Riltse's 'Bogus Hole' to Buenos Aires; the story of the obsessive lover Adele Hugo; the tragic fate of Rimini's junior-school teacher. After about 400 pages, the novel is even good enough to recap an earlier sequence, presumably fearing that the portrayal of amnesia may have brought it on in the reader.

Please visit SPLALit aStore

Argentine Literature

Enrique Vila-Matas - Bartleby & Co. and Montano's Malady.

Roberto Ontiveros reviews Enrique Vila-Matas' Bartleby & Co. and Montano's Malady.

Enrique Vila-Matas writes novels about those who can't write, those who can write but choose not to and those who wrote until they woke up one day and discovered they no longer could. His book "Bartleby & Co." is a respectful devotion to all who engage in the grand "No" of literature, who spurn the static word for politics, ennui or maybe even a chance at actual living. Because writing, which demands solitude and often leads to misanthropy, stands outside of life.Read More

In the guise of an assemblage of footnotes to a study of an invisible text, our narrator — a disgruntled desk clerk with a humpback who has no luck with women — explores his fascination with writers such as Rimbaud, Becket and Kafka, who, like Melville's Bartleby the Scrivener, prefer not to further engage in the pingpong of literature. Our hero sacrifices his mind and employment for this project. He takes a trip to New York on a phony sick leave and is torn between his desire to run up to a man he is sure is J.D. Salinger and his desire to proposition the young woman standing near him. Upon realizing that the two are an item, he balks at the unfairness of the world and decides to listen in so he can stay apprised of the reclusive author's newest work.

This book is no labyrinthine joke but rather a genuine puzzle: Can a reader not at least marginally enthralled with these authors find entertainment in a book about what they haven't written?

"Bartleby & Co.," which was published in Spain in 2001 and translated into English in 2004 (the New Directions edition is a recent paperback reissue), is Vila-Matas' first book to appear here. It falls into a line of honorable literary experiments: During the cold war the Polish writer Stanislaw Lem put together an entire book composed of reviews of nonexistent books. More recently, the late writer Roberto Bolaño created "Nazi Literature in the Americas," an encyclopedia of fake fascist writing. But everything here is genuine — genuine hearsay about the proto-surrealist Marcel Duchamp, grounded criticism of Guy Debord's Situationist movement and real debate over the very reasons for writing.

Even the made-up material rings with authenticity. There is a touching and perplexing moment when our scholar of absence asks the proprietor of a bookstore why he doesn't write.

Please visit SPLALit aStore

Spanish Literature

Mexican Writers on Writing edited by Margaret Sayers Peden

Edward Hirsch reviews a new collection of Mexican texts, Mexican Writers on Writing edited by Margaret Sayers Peden

Please visit SPLALit aStore

Mexican Literature

The history of Mexican literature, at least of that written in the Spanish language, begins during the Conquest with "chronicles and letters," explains Margaret Sayers Peden, "a fascinating body of materials in which their authors report, not infrequently with exaggeration, their own feats, along with the wondrous landscapes and cities and peoples they encounter." Novels and plays and poems came much later, once Spanish dominance was established. But "it seems inevitable," Peden writes, "that future scholars and historians will define the twentieth century as Mexico's Golden Age." Three giants -- Octavio Paz, Carlos Fuentes and Juan Rulfo (all of whom are included in this collection) -- ruled the field, but many other writers (and a nascent publishing industry) contributed to the cultural richness, which has only in recent decades been translated into English.Read More

Please visit SPLALit aStore

Mexican Literature

Tuesday, July 17, 2007

Pablo de Santis - Interview

Los escritores somos especialistas en todo y en nada. Construimos ilusiones de conocimiento, tomamos de la realidad algo y vamos construyendo con eso una manera de conocimiento inventado. Así, un poco con las astillas de la historia y los mapas del París real armé un París de fábula. Tomo lo que me sirve para la historia, no me gustan las informaciones inútiles, sólo aquello que es expresivo, lo que se corresponda con el mundo imaginativo.Read More

Please visit SPLALit aStore

Argentine Literature

Friday, July 13, 2007

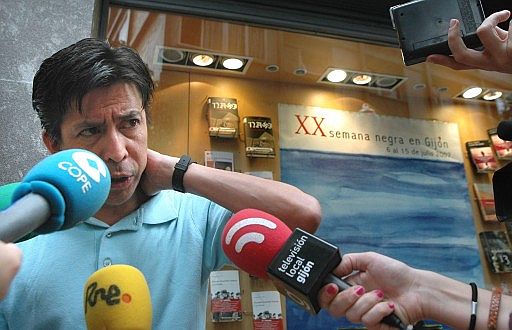

Mexican writer Juan Hernández Luna won the Hammett Prize, during the "Semana Negra de Gijón" (Gijón's Dark Week) for best Crime Novel written in Spanish with "Cadáveres de ciudad", a dark story set in Mexico City.

Mexican writer Juan Hernández Luna won the Hammett Prize, during the "Semana Negra de Gijón" (Gijón's Dark Week) for best Crime Novel written in Spanish with "Cadáveres de ciudad", a dark story set in Mexico City.Cuban author Amir Valle won the Rofolfo Walsh prize for the best nonfiction work with his book "Jineteras", where he draws up a crude image on prostitution in Havana.

Please visit SPLALit aStore

Latin American Literature

Thursday, July 12, 2007

Malta con Huevo - Trailer

Malta con Huevo was directed by Cristóbal Valderrama and produced by Alberto Fuguet.

Please visit SPLALit aStore

Chilean Cinema

Peruvian writer Alonso Cueto (Lima, 1954) presents, in Colombia, his new novel "El susurro de la mujer ballena".

Peruvian writer Alonso Cueto (Lima, 1954) presents, in Colombia, his new novel "El susurro de la mujer ballena".La obra, finalista del Premio Planeta-Casa de América, relata la historia de dos amigas radicalmente opuetas que reviven los años del colegio.Read More

"La pared era mi único consuelo, ¿sabes? A veces me daba por escribir algo en la pared, y lo borraba. Escribía por ejemplo 'Mierda mierda mierda' y después lo borraba. Pero después me metía en el baño y lloraba y golpeaba la pared con la mano y una vez la mano me empezó a sangrar", le cuenta Rebeca a Verónica después de encontrarla casualmente en un avión. Habían sido las mejores y más inseparables amigas en los ya lejanos años de colegio.

Este encuentro es el que da comienzo a El susurro de la mujer ballena, la novela con la que el escritor peruano Alonso Cueto se llevó el segundo lugar del Premio Planeta-Casa de América 2007.

Please visit SPLALit aStore

Peruvian Literature

Tuesday, July 03, 2007

Roberto Bolaño - The Savage Detectives and The Last Evenings on Earth

Ben Richards reviews Roberto Bolaño's Last Evenings on Earth and The Savage Detectives

Ben Richards reviews Roberto Bolaño's Last Evenings on Earth and The Savage Detectives The poet's troubled odyssey is the dominant theme of both Last Evenings and Bolano's novel The Savage Detectives (both brilliantly translated). The latter begins in the 1970s in Mexico City, where two poets - Arturo Belano and Ulises Lima - are leading a literary movement called visceral realism. The first part of the novel is told in diary form by one of their young disciples - a puzzling figure not remembered by others in the movement - who interrupts observations on Belano and Lima to recount his early sexual encounters. This section ends abruptly with the poets, in the company of a whore fleeing her pimp, commandeering a car and heading for the desert. Their quest is to find a lost poet from an earlier literary movement, the wonderfully named "stridentists" (lost, missing, exiled and orphaned poets are - along with prostitutes - a key motif in Bolano's work).Read More

It is a shaggy dog story, but is the dog chasing its nose or its tail? The second part of the novel gives a dazzlingly different perspective (or multiple perspectives) on Belano and Lima by introducing a series of diverse witness testimonies from those who encounter them. These include descriptions of their behaviour on their return from the desert and the various roads of madness and ruin that they travel. In the final phase, we return to the first youthful narrator, who gives an account of the dramatic events during the quest for the lost poet.

Bolano is not reticent about mixing his life story - or at least a mythologised version of it - with his work. He pops up in various guises, principally as the Chilean Arturo Belano, so it is worth pausing to consider his biography. Bolano left Chile when young to live in Mexico, returning briefly to his home country just before the Pinochet coup; he was briefly detained but then reverted to a nomadic, bohemian, heroin-fuelled existence as a vagabond poet before settling in Spain. He turned to prose to pay the rent, and there were times in reading The Savage Detectives when I wondered if it represented Bolano's revenge on the novel for this enforced career choice. Exercised by the "who's-the-daddy?" bickering that is a lamentable aspect of Latin American literature, he was not short of acerbic opinions on his peers. He was scornful of Isabel Allende, whose healthy sales figures and ability to smile on her book jackets have irritated more than a couple of his male contemporaries too. At times the obsession with the role of enfant provocateur , which surfaces repeatedly in Bolano's fiction, becomes tiresome. In the short story "Dance Card", he assumes the mantle of literary drama queen to demand rhetorically: "Do we have to come back to Neruda as we do to the cross, on bleeding knees, with punctured lungs and eyes full of tears?" And it is difficult to resist a shrug. Well, not if you don't want to, Roberto.

Please visit SPLALit aStore

Chilean Literature

Roberto Bolaño

Francisco Goldman reviews Roberto Bolaño's The Savage Detectives, Distant Star, Last Evenings on Earth and 2666.

Francisco Goldman reviews Roberto Bolaño's The Savage Detectives, Distant Star, Last Evenings on Earth and 2666."A writer's patria or country, as someone said, is his language. That sounds pretty demagogic, but I completely agree with him...." That is from Roberto Bolaño's acceptance speech for the 1999 Rómulo Gallegos Prize, an award given by the government of Venezuela for the best Spanish-language novel of the year in Latin America or Spain. Bolaño won the prize for The Savage Detectives, his sprawling, exuberant account of two Latin American poets over twenty-some years, which made him a literary celebrity and established him as one of the most talented and inventive novelists writing in Spanish. Bolaño was routinely asked in interviews whether he considered himself Chilean, having been born in Santiago in 1953, or Spanish, having lived in Spain the last two decades of his life, until his death in 2003, or Mexican, having lived in Mexico City for ten years in between. One time he answered, "I'm Latin American." Other times he would say that the Spanish language was his country.

"Although I also know," he continued in his acceptance speech,that it's true that a writer's country isn't his language or isn't only his language.... There can be many countries, it occurs to me now, but only one passport, and obviously that passport is the quality of the writing. Which doesn't mean just to write well, because anybody can do that, but to write marvelously well, though not even that, because anybody can do that too. Then what is writing of quality? Well, what it's always been: to know how to thrust your head into the darkness, know how to leap into the void, and to understand that literature is basically a dangerous calling.

The inseparable dangers of life and literature, and the relationship of life to literature, were the constant themes of Bolaño's writings and also of his life, as he defiantly and even improbably chose to live it. By the end of that life, Bolaño had written three story collections and ten novels. The last of these novels, 2666, was not quite finished when he died of liver failure in 2003, which did not prevent many readers and critics from considering it his masterwork. It is an often shockingly raunchy and violent tour de force (though the phrase seems hardly adequate to describe the novel's narrative velocity, polyphonic range, inventiveness, and bravery) based in part on the still unsolved murders of hundreds of women in Ciudad Juárez, in the Sonora desert of Mexico near the Texas border. (2666 is currently being translated into English and is due to be published next year by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.)

Yet the writer with whom Spanish-language critics have often compared Bolaño is the Argentine Jorge Luis Borges, renowned for his singular bookishness, and for the metaphysical playfulness, erudition, and brevity of his entirely asexual writings. With those comparisons critics have wanted, partly, to emphasize their sense of Bolaño's significance, for Borges is probably the only Latin American writer of the past century whose greatness seems uncontested by anybody, though the more you read Bolaño, the more interesting and appropriate the comparison between the two writers becomes. Bolaño revered Borges ("I could live under a table reading Borges"). He would have been happy, Bolaño told an interviewer, to have led a life like Borges's—relatively sedentary, devoted to literature and a small circle of like-minded friends, "a happy life." But Bolaño lived most of his life in another manner. "My life," he said, "has been infinitely more savage than Borges's." Read More

Please visit SPLALit aStore

Latin American Literature

Nada by Carmen Laforet

Alberto Manguel reviews Carmen Laforet's Nada.

Please visit SPLALit aStore

Latin American Literature

During my adolescence, in the Buenos Aires of the 60s, my friends and I believed that the only worthy literature in Spanish was written in Latin America, an arrogant opinion that seemed confirmed by the wealth of the writers brought on by the so-called boom, such as Julio Cortazar and Gabriel Garcia Marquez. The literature of Spain, smothered by the civil war, appeared to have survived only in its poetry, and not at all in its fiction. Then, one day, we discovered Nada by Carmen Laforet and realised how mistaken we had been. Written quickly, in barely a few months, expressly to take part in the first Nadal literary prize (which it won), Nada (Nothing) took the Spanish readership by storm. First published in 1944, barely five years after the end of the civil war, it now appears in English for the first time, in a fluid translation by Edith Grossman.

The author was 23, and it is hard to understand how someone so young, within the isolation of Franco's Spain, should have been able to produce such an accomplished novel, so powerful in its story and so polished in its style. With Nada, Laforet broke Spanish literature free from the cumbersome shadow of 19th-century prose and the cold, censored rhetoric of Spanish fascism. Read in Argentina before the military dictatorship, it spoke to us of a state of fear and oppression that we could not know was threatening us; read in English today, it retains, within the now alien world it depicts, a note of warning and salutary unease.

Nada tells the story of Andrea who, like Laforet herself, leaves her native Canary Islands at the age of 18 to live in her grandmother's house in Barcelona, with the intention of studying literature at the university. Besides her grandmother, the house is inhabited by her two uncles, Juan and Roman, her aunt Angustias, the maid Antonia, and Juan's wife, Gloria, plus a menagerie of cats, an old dog and a parrot. Andrea is a sort of 20th-century Alice, fallen into a Wonderland whose characters and rules she fails to understand, and whose maze of family dramas she must reluctantly follow, beset by narrow-mindedness, poverty, violence and hunger.

Gloria has been Roman's mistress before and after her marriage to Juan, the straight-laced Angustias has been having an affair with her married boss, the grandmother (who never sleeps) fawns over her two sons while disdaining her daughters - three of them managed to leave the dreadful house long ago, including Andrea's mother. The maze spreads outside the house, into the postwar city, into the gambling den kept by Gloria's sister, into the university circles of would-be artists, into the dark streets and crumbling churches. Even Andrea's relationship with her best friend Ena provides another twist in the course, when Andrea discovers that Ena's mother was once humiliated by her uncle Roman and that Ena's friendship serves to accomplish a terrible revenge. Read More

Please visit SPLALit aStore

Latin American Literature

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)